Here is a great story about how a musician got their start with AYS from their blog.

AYS Alumnus Michael Ryan Armstrong has one of the most interesting and exciting “AYS stories” that I have heard from any AYS musician or alumni to date. His AYS “audition” was anything but traditional, which seemed to parallel his untraditional path of becoming a successful musician and professional in the music industry. Without knowing much about Michael before the interview, I left with a whole new set of knowledge about AYS and how being in the orchestra can really launch a young musician’s career in ways that they never thought possible.

Michael is a true Angeleno. He was born and raised in Los Angeles by his musical parents and has lived in LA ever since. His mother is a French horn player who attended USC, and his father is a trumpet player who had his own band and would often get gigs playing with big name bands such as the Beach Boys. “Some of my earliest musical memories are hearing my parents practicing and talking about music. I also remember them taking me and my brothers to lots of rehearsals and concerts.”

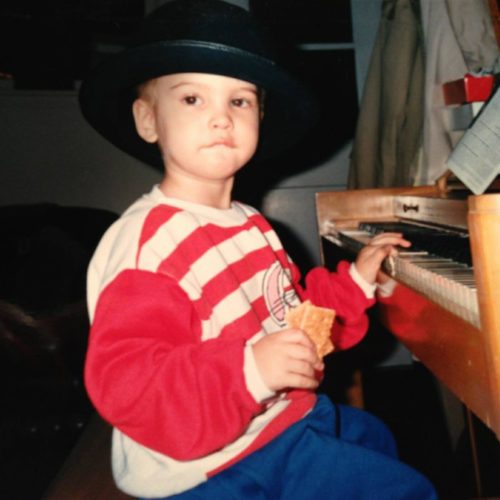

With music being a foundation of the Armstrong family, Michael knew at a very young age that he was destined to have a career in the music industry. He started his own musical journey by first playing the piano, because it was an instrument that was always around and a strong presence in his home. “I would practice by ear a lot as a kid, and I would always see the keyboard in my mind when I heard music.” He started to take formal piano lessons when he was 7 years old, and continued throughout his teen years, studying with Connie Barnes Kuhne and Edward Francis.

With his family being brass players, he also learned to play trumpet. “This was a right of passage for my family. It was also nice because my younger brother Sam, also an AYS alum, plays the trombone. So, when we were younger we played in lots of youth orchestras and other groups together.” Because Michael and his siblings were homeschooled, they had the flexibility to practice a lot and participate in many different bands and orchestras. “Our house was kind of like a music bootcamp.”

Along with being a piano and trumpet player, Michael found another passion in his teens, which was conducting. While attending summer music camps and youth orchestras, he started talking to the conductors about conducting and was encouraged to give it a try. At the age of 17 Michael started private conducting lessons. His teachers included Larry Livingston from USC, Brad Keimach from Glendale Youth Orchestra, and Bill Benson of the Conejo Valley Youth Orchestra.

Over the years, conducting became a bigger and bigger part of his life. “I’ve been very blessed to be able to conduct quite a bit, primarily with youth orchestras, community orchestras, and most recently at Thomas Aquinas College in Santa Paula. I’m very much looking forward to getting back on the podium once concert halls start to open up again.”

When it came to launching his career in music, Michael credited the influence from his parents and also American Youth Symphony. Instead of attending college for music performance, Michael explained that his time in AYS contributed a great deal to his musical education. “AYS provided me with the networking and tools I needed in order to be prepared for higher-level work in the music industry.”

From the very beginning of his AYS journey, Michael was already being thrown in with one of the greatest composers of our time, John Williams.

“My ‘audition’ into AYS is kind of a funny story. My younger brother Sam joined AYS at the young age of 16 as a trombone player, and I used to drive him to and from rehearsals. One time I decided to stay for a rehearsal and hear the orchestra play for the first time. They were playing Brahms’ Symphony No. 1 and I remember thinking ‘Wow, these kids are really good,’ and leaving feeling really proud of my brother for being a part of such a prestigious orchestra.

Some time later, I was sitting in on a rehearsal for an upcoming concert where John Williams would be conducting his own music. I noticed that there was no one playing keyboards for the rehearsal — apparently the person who was supposed to play had not shown up. I asked the orchestra manager if he would like me to cover the parts for the rehearsal and he said that I was welcome to. After getting through the rehearsal, I was asked to play on the concert. One of my best memories is of the dress rehearsal when John Williams himself came to rehearse us. There was a particularly difficult solo passage for celesta on the opening of Harry Potter. We played through that section and John Williams suddenly stopped. He turned around to where I was sitting behind him and said, ‘Nice.’ That was a big relief, and that’s how I started playing with AYS.”

This John Williams concert was Michael’s first of many playing piano and keyboards, and organ for AYS. During his tenure of seven years with the orchestra (2008-2015), Michael had the opportunity to play at some of LA’s finest concert halls and work with some of his favorite conductors including James Conlon, Alexander Treger, and David Newman, who is also an AYS Board Member and alum.

“I’m really grateful for Dave Newman because he taught me a lot about music technology and he even helped me get a discount on my first MacBook Pro laptop, which we used to create all the different keyboard sounds for the film music concerts. Dave would work closely with me and helped develop my technical skills which are so essential for having a successful career. Billy Sullivan [also an AYS Board Member] was also a huge influence. They both helped me to understand the technology side of music, which is critical for anyone interested in recording work. Those guys were my heroes and mentors.”

AYS also provided Michael with his first experiences playing music live-to-picture. “The film music concerts were just unreal. Playing film music is quite different from playing classical repertoire, and that kind of experience is extremely hard to come by.”

Playing orchestral music with world-class musicians and conductors, being exposed to influential people in the field, and learning the technical skills related to film music were just a few things that Michael took away from his experience in AYS. He explained that AYS also helped him build his confidence.

“I was often a little insecure about not being in school or having a degree, because that’s something that people always ask about. But once I was in AYS there was a new level of respect that people showed me. It was a big thing for me that really boosted my confidence and made me feel very proud of what I was doing.”

Since his final season with AYS in 2015, Michael has kept up with all of his interests and passions, with music being at the core. Through our conversation, I learned that he is very versatile and seems to be a jack of all trades in the field! He owns his own business, Armstrong Orchestral, which provides music contracting services, and specialty music printing for composers and orchestras nationwide. After building up his business for over 10 years, he recently had to shift his services to include more digital offerings, such as graphic design and video editing, because of the COVID-19 pandemic and closure of concert halls. With all the virtual concerts happening, he is busier than ever and happy to see where his latest projects are taking him…including working on AYS’ virtual productions this year as our score reader.

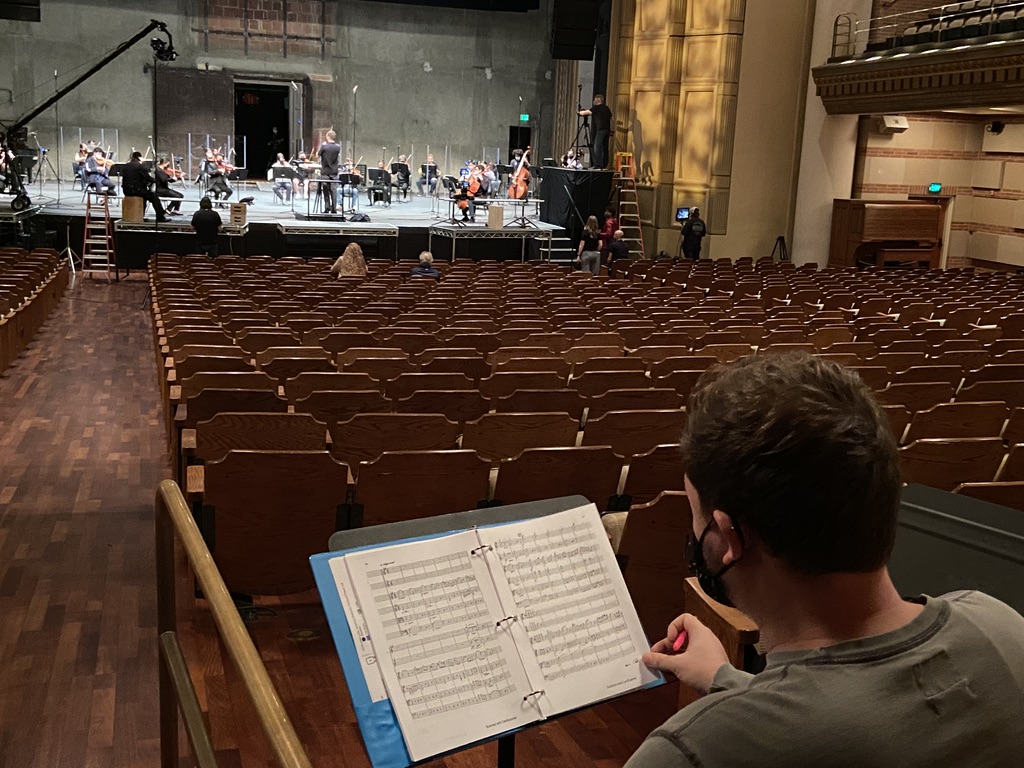

AYS first hired Michael to be our score reader for the production of Jessie Montgomery’s Starburst and Benjamin Britten’s Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge for our Fall Concert in October 2020. Currently, he is working with us again on the production of our 56th Annual Gala to be aired on June 3, 2021. As our score reader, he works very closely with Music Director Carlos Izcaray and Director of Photography Philip Holahan throughout the duration of the production process. He acts as the musical consultant to Philip, helping him strategize where to place the cameras and focus on certain musicians for specific parts of the music, as well as communicating with Maestro Izcaray.

“I had to figure out what being a score reader meant, too, during this process. Essentially, when you are planning to film a concert, you have to first decide where your cameras are going to be placed. That will be different for every piece, and you have to look into the score to decide what is most important. There are so many moving parts of an orchestra, for example, different solos and points of conversation between different sections. So I help in identifying those parts with Philip so that we can take the viewers on an interesting journey through each piece.”

Michael working as AYS’ Score Reader on May 8, 2021 at UCLA’s Royce Hall.

Prior to recording day, Michael reviewed the stage plots and camera placements for the different pieces, to make sure they work together as a whole. He also developed and made a shot list with Maestro Izcaray and Philip. On the day-of, Michael was on a headset and provided cues to the film crew while the orchestra was playing. It’s very similar to how a stage manager would give cues to the lighting and sound design team during a theatrical performance. “I’m basically the musical translator for the film crew.”

If that weren’t enough already, Michael explained that the work after the content is captured is the most crucial. “I sit with the main video editor and go through every shot with the score. Philip has the real eye for the shots and vision for how everything should look, but I help to ensure that we are looking at the right instruments at certain parts in the score. I also help verify that the music is synced with the film and keeping a close eye on syncing with the bows, conductor, etc.”

After capturing the orchestra’s performance on May 8, 2021, Michael, Philip, Maestro Izcaray, and other editors have a few weeks to cut the four pieces being broadcast for the 56th Annual Gala on June 3rd.

After learning about all of Michael’s talents, I asked him what his hopes are for the future. He responded that 2020 brought new passions of his to light, including producing film concerts for orchestras. “I think this virtual way of making and sharing music is going to be something that many orchestras will incorporate into their regular concert seasons, even after concert halls are open again. During the pandemic I have discovered so many new orchestras from the productions they have shared online. I hope we continue to see a hybrid of live concerts and virtual ones in the future.”

I thought this vision also resonated with one of Michael’s biggest lessons he learned from his parents. They taught him that a music career is a difficult path and things won’t always turn out exactly how you expect — but what matters most is that you keep adapting and stay with it for the long run.

We should continue to expect huge things from Michael as he continues to explore what it means to have a career in music with his multiple talents and interests. For young musicians out there, I hope Michael’s story inspires you to forge your own path in the music industry.